It seems it doesn't matter what time period or continent I escape to; girl meets girl can never just happen in peace.

-

-

African Women Entrepreneurs in Tech “Lean In” for Social Media Week

What does "Leaning In" look like for African women entrepreneurs in tech? Nigeria's leading women in tech weigh in on dos, don'ts, and lessons learned.

-

The Revolution Will Be Online: Spectra Speaks with Jay Smooth on Activism in the Digital Era

I'm on a panel with one of my favourite video bloggers, Jay Smooth of Ill Doctrine! At "The Revolution Will Be Online" we'll be chatting about a topic that speaks to the crux of all my work: the power of media, technology, and online conversations to propel change in the…

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Love Is My Revolution - Special Series - Spirituality - The Political, Personalized

Love as a Revolution Totally Sucks

Ever had one of those days when your ideals, your spiritual beliefs, your politics, your internal moral compass just feels broken? Well, I've been having those days a lot lately. Here's to raising a white flag, and hitting rock bottom, so you can find your way back up.

-

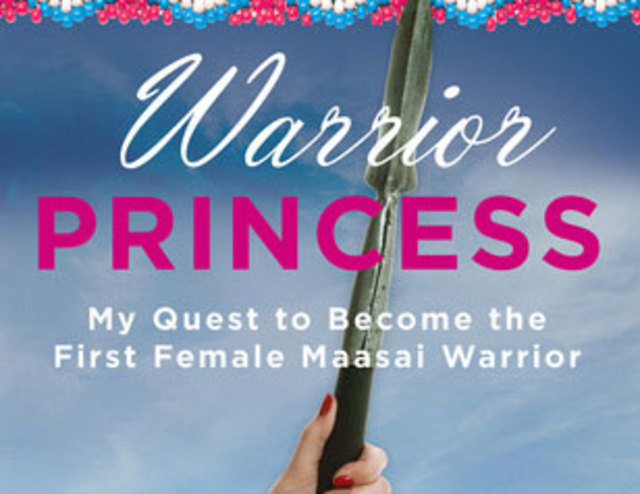

Dear Western Saviorists, Stop Reducing Africa to a Play Pen for Your Personal Development

From Colorlines: "When Mindy Budgor was 27 years old, she apparently tried to find meaning in her life by temporarily ditching her wealth in Santa Barbara and jetting over to hang with the poor people of Kenya." Read the full story, and my less than tempered response to yet another…