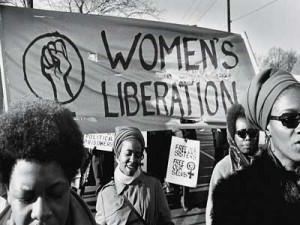

Yesterday, I took part in the MA Women United Against the War on Women rally at Boston City Hall.Â

Across the US, thousands of men, women and children gathered in front of municipal buildings to voice their outrage at recent state and federal initiatives to propose and/or implement anti-women measures, including the GOP’s attempt to redefine rape, making abortions illegal or virtually inaccessible to low-income women, and removing government mandates for companies to include birth control coverage in the health insurance they offer to employees.

Despite the fact that it took challenging the white women organizers to include more women of color in their speaker lineup — as a little birdie told me — I was honored to be invited to participate, and share the stage with fellow women’s rights activists and feminists, Jaclyn Friedman, Sarah Jackson, @graceishuman, Idalia, and even Norma Swenson, reknowned author of the book, Our Bodies, Ourselves.

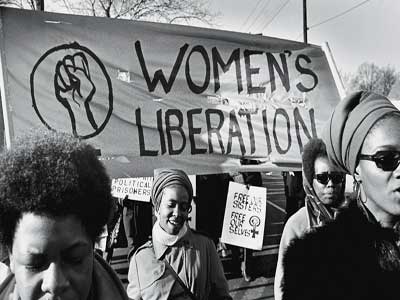

I found myself thinking about the concept of “unity,” and the fact that so many women of color, immigrants, transgender women etc are often left out of mainstream women’s movements. But this isn’t news to me, nor to my mentors separated from my experience by four whole decades — mentors who fought so that I would have something different to say to white women “united” for (white) women. It breaks my heart to tell them that we’re still having the same conversations after all their sacrifices.

I found myself thinking about the concept of “unity,” and the fact that so many women of color, immigrants, transgender women etc are often left out of mainstream women’s movements. But this isn’t news to me, nor to my mentors separated from my experience by four whole decades — mentors who fought so that I would have something different to say to white women “united” for (white) women. It breaks my heart to tell them that we’re still having the same conversations after all their sacrifices.

Hence, for the rally, I decided to have an honest conversation about marginalization with the crowd via a call-and-response speech I partly improvised. Here’s the message I gave, in poem-ish form.

Post-Rally Reflection:Â To speak from a place of anger doesn’t always mean to speak from a place that is without love. How emotional I became when speaking to the rally yesterday has everything to do with how much I love my comrades of all shades and stripes, fellow women, my sisters-in-arms. And their response to my calling out to them, “My Sisters in Arms” with “We Are Listening” helped me through my anger to the other side… hope.

—-

When I was younger, I dreamed of being part of a revolution.

I imagined it would feel very much like it did in the movies, like Braveheart for instance:

Mel Gibson riding back and forth on horseback, pumping his fist in the air

as he inspired the army before him to FIGHT for their freedom,

we would win this war together.

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

Like every big budget Hollywood movie,

I’d be the handsome, mysterious, emotionally constipated protagonist

who never really wanted to fight,

but live happily ever after in the same village of my beautiful virgin wife-to-be…

until one day,

the fight came to me

and wiped away the smiles of my love, my family, my home.

Only THEN, would I charge forth, my spirit consumed by purposeful rage

and the moment — the moment I’d dreamed of having my entire life — would arrive…

the epic war speech.

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

Yes, like Braveheart, my heart would be re-forged in stone; I would feel a bond with my comrades united in arms (and social media channels) like I’d never felt before.

And in that moment, against the violins and horns of a moving Hans Zimmer film score,

in the faces of all my sisters standing before me,

I would remember:

the battle, the war, the revolution

isn’t about me,

the battle, the war, the revolution

isn’t about them

but about US.

We would stand UNITED against whatever forces dared to oppose us,

and charge forth together.

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

But the revolution hasn’t quite turned out like the Hollywood movie I’d imagined it would be.

For one, it actually never occurred to me that I wouldn’t be riding a horse.

Mel Gibson turned out to be one of the biggest bigots of all time.

And sexual assault has caused too much pain to the women I love to perpetuate the idea that virginity is a prize to be won,

not when rape is still being used as a mass weapon of war.

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

It’s true, the revolution hasn’t quite turned out the way I dreamed it would be,

it never occurred to me

that battle after battle,

rally after rally,

I would find myself standing in front of a sea of white women who don’t look like me,

having to keep reminding them that:

United we stand, Divided we fall.

United we stand, Divided we fall

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

I know why we’re here.

There is a war on women happening,

We’re angry — and we’ve had enough.

On that we agree.

But today, I want to make sure we do more than just agree.

I want to make sure we’re paying attention to our subconscious definition of “weâ€

I want to make sure we’re paying attention to who is missing.

Look around you, my Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

I ask you to consider,

is the women’s movement making a stand, or falling into pieces?

Are we uniting through our differences so that we can be stronger?

Or reaching for something way less grand,

with way less hands,

hoping that our “good intentions†will pay off if we just wait a little longer?

Which members of this army — of our family — are missing?

Where are the voices of low income women of color?

Where are the voices of transgender women?

Where is the rest of our family?

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

This women’s movement shouldn’t just voice the concerns of women who are pissed

that they may have to pay for birth control out-of-pocket,

but the concerns of low-income women who would have no access to birth control, period

because they rely completely on government-mandated coverage,

I know you agree, but…

My Sisters-in-Arms, are you listening?

(We Are Listening!)

we cannot profess to be building a movement for ALL women,

we cannot claim that we are UNITED against anything — especially not a war on women

when too many women of color, transgender women, women with disabilities — members of our family, are missing.

My Sisters-in-Arms…

(We Are Listening!)

When we picture the women’s movement what faces do we see?

What voices do we hear?

And are they reflected in our choices? In our larger strategy?

Are transgender women a part of this movement?

Have we done our jobs to make that clear?

If so, where is the outrage when transgender women are murdered at an alarming rate in this country?

Where is the feminist takedown when — even in death — the media refers to our trans sisters with male pronouns and the media suggests that their very existence warranted their assault and murder?

Too many transgender women are being left behind.

Too many members of our family are dying.

Too many members of our family are being  tortured and incarcerated, simply for surviving,

Just because we’re too busy “uniting” to look behind.

My Sisters-in Arms

(We Are Listening!)Â

You must do better.

We must do better.

If I’ve learned anything about real-life revolutions

it’s that they sometimes can take on the form of the war you’re fighting.

it’s that it matters less what you’re fighting for, but who is fighting with you

The War on Women needs to mean more than reproductive justice for middle class white women.

The War on Women needs to mean more than the debate over abortion and birth control.

The War on Women must mean to us the impact of racism on women of color and our sons.

The War on Women must mean to us the impact of racism, sexism, and homophobia on transgender women of color.

The War on Women must mean to us the impact of un-checked privilege and ignorance within  our movement.

The War between Women is real.

And until we can be brave enough to face the truth —

that we have to END the war over who counts as “women” amongst ourselves

we are NOT united.

My Sisters-in Arms

(We Are Listening!)Â

We are NOT united, yet.

But I know we can get there.

I believe in you, my Sisters-in Arms

(We Are Listening!)Â

I know we can get there.

And so IÂ dare to dream of the day

when I can finally show up to rallies and protests

and not have to say,

“Where are my sisters?”

but “Here are my sisters, united.”

I dare to dream of the day when we can all feel the impact of true sisterhood

and unleash the power of sisters-in-arms, united,

against those who dare to challenge our quest for liberation.

My Sisters-in Arms

(We Are Listening!)Â

I believe in us.

My Sisters-in Arms

(We Are Listening!)Â

We are not united, now.

Let’s do the work, now

To make sure that one day, we will be.

And when that day comes,

My Sisters-in Arms

(We Are Listening!)

God help them.

Spectra is an award-winning Nigerian writer, women’s rights activist, and the voice behind the African feminist media blog, Spectra Speaks, which publishes global news and opinions about all things gender, media, diversity, and the Diaspora.

Spectra is an award-winning Nigerian writer, women’s rights activist, and the voice behind the African feminist media blog, Spectra Speaks, which publishes global news and opinions about all things gender, media, diversity, and the Diaspora.

She is also the founder of Queer Women of Color Media Wire (www.qwoc.org), a media advocacy and publishing organization that amplifies the voices of lesbian, bisexual, queer, and/or transgender women of color, diaspora, and other racial/ethnic minorities around the world.

Follow her tweets on diversity, movement-building, and love as a revolution on Twitter @spectraspeaks.

Calm down.

Calm down. The straw that broke the camel’s back was the day I forgot to pee before I got home. I’d been out at a restaurant with friends and it had slipped my mind. I’d ordered a soup for dinner, so around 10 pm, I really needed to go. But it was dark outside, the night belonged to the cockroach, not me. So rather than brave the inevitable face off in the bathroom, I held my pee… for 8 hours.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was the day I forgot to pee before I got home. I’d been out at a restaurant with friends and it had slipped my mind. I’d ordered a soup for dinner, so around 10 pm, I really needed to go. But it was dark outside, the night belonged to the cockroach, not me. So rather than brave the inevitable face off in the bathroom, I held my pee… for 8 hours.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the internet’s sensationalized debate over Zoe Saldaña playing Nina Simone in a Hollywood biopic:

A few weeks ago, I wrote about the internet’s sensationalized debate over Zoe Saldaña playing Nina Simone in a Hollywood biopic:  Case in Point:

Case in Point:

I found myself thinking about the concept of “unity,” and the fact that so many women of color, immigrants, transgender women etc are often left out of mainstream women’s movements. But this isn’t news to me, nor to my mentors separated from my experience by four whole decades — mentors who fought so that I would have something different to say to white women “united” for (white) women. It breaks my heart to tell them that we’re still having the same conversations after all their sacrifices.

I found myself thinking about the concept of “unity,” and the fact that so many women of color, immigrants, transgender women etc are often left out of mainstream women’s movements. But this isn’t news to me, nor to my mentors separated from my experience by four whole decades — mentors who fought so that I would have something different to say to white women “united” for (white) women. It breaks my heart to tell them that we’re still having the same conversations after all their sacrifices. Spectra is an award-winning Nigerian writer, women’s rights activist, and the voice behind the African feminist media blog,

Spectra is an award-winning Nigerian writer, women’s rights activist, and the voice behind the African feminist media blog,

Originally posted at

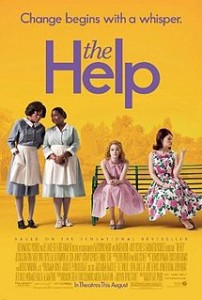

Originally posted at  Out of 9 feature films, just one of them is based on a black South African narrative:Â The Secret, a film about a married man in denial about his sexuality. This feature film is being paired with Paving Forward, a 16-minute short about the evolution of gay rights through the eyes of a lesbian love story. The pickings are slim for black South Africans eager to see their experiences reflected on film, but to be fair, these selections are part of just the first installment of the festival’s three-part format.

Out of 9 feature films, just one of them is based on a black South African narrative: The Secret, a film about a married man in denial about his sexuality. This feature film is being paired with Paving Forward, a 16-minute short about the evolution of gay rights through the eyes of a lesbian love story. The pickings are slim for black South Africans eager to see their experiences reflected on film, but to be fair, these selections are part of just the first installment of the festival’s three-part format. The Secret (Imfhilo): The closet was never fashionable, but living the DL is super trendy. Down Low means living under the radar as a straight man having gay sex, or having two separate lives. In Fanney Tsimong’s soap opera-like story of a gay man’s affair with a closeted married man, it gets neatly transported across the Atlantic from the US into aspirant township life. Generations actor Sipho “C-ga†Masebe’s plays Mandla, openly gay, good looking and searching for love. He bumps into old college buddy Thoriso at a birthday party. Thoriso is married to the controlling Thuli, bent on nothing so much as getting ahead in the upwardly mobile world of the BEE nouveau riche. As Mandla chases Thoriso, worlds and assumptions are overturned and lives altered forever. The climax of the film is a credit to the writer – there’s no preachy quick-fix, rather a reality check of what’s really going on out there. Intriguing contemporary South African cinema. (Dir: Fanney Tsimong SA / 2011 / 45min)

The Secret (Imfhilo): The closet was never fashionable, but living the DL is super trendy. Down Low means living under the radar as a straight man having gay sex, or having two separate lives. In Fanney Tsimong’s soap opera-like story of a gay man’s affair with a closeted married man, it gets neatly transported across the Atlantic from the US into aspirant township life. Generations actor Sipho “C-ga†Masebe’s plays Mandla, openly gay, good looking and searching for love. He bumps into old college buddy Thoriso at a birthday party. Thoriso is married to the controlling Thuli, bent on nothing so much as getting ahead in the upwardly mobile world of the BEE nouveau riche. As Mandla chases Thoriso, worlds and assumptions are overturned and lives altered forever. The climax of the film is a credit to the writer – there’s no preachy quick-fix, rather a reality check of what’s really going on out there. Intriguing contemporary South African cinema. (Dir: Fanney Tsimong SA / 2011 / 45min)