I didn't sign into Facebook that morning. I knew what I'd see; a timeline of status updates and cropped purple photos for Spirit Day; a timely performance of empathy. I knew, too, that my Facebook feed, practically segmented into Lists, including one for "Nigerian", "College" and "Queer" would vary in…

-

-

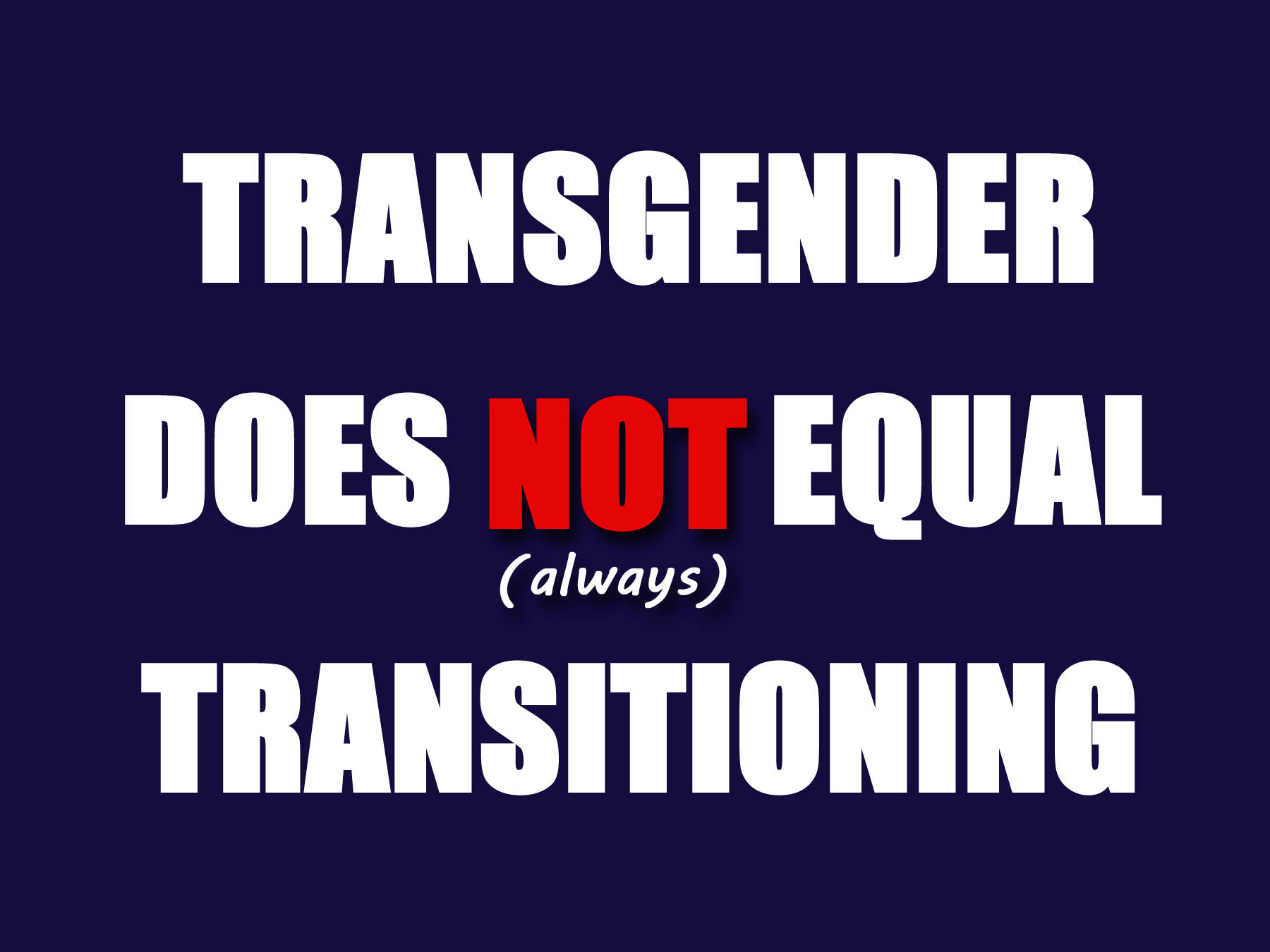

PSA For Transgender Awareness Week: Transgender Doesn’t (Always) Equal Transitioning

About a month ago, I wrote a write on my tumblr account in response to numerous inquiries from people right after I disclosed that I was gradually accepting a shift in my gender identity (i.e. feeling way more masculine than I do feminine) about when I would be transitioning. Na…

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Community Organizing - Gender and LGBT Issues - QWOC+ Boston - Race, Culture, Ethnicity

Queer Women of Color Still Face Racism During Pride, Among Other Things

Activism, for so many of queer women of color, is a constant negotiation of which ism to address. We don’t have the luxury of snubbing everyone that offends us, or we would have no where to go. We can't -- and shouldn't have to -- fight everyone. As a direct…