BET.com interviews me about my work as a media activist focusing on gender and LGBT issues in Africa. The piece, which was very positive and optimistic, prompted some thoughts about what "good" media activism means to me. Surprisingly "good" media has nothing to do with it. Read the interview, and…

-

-

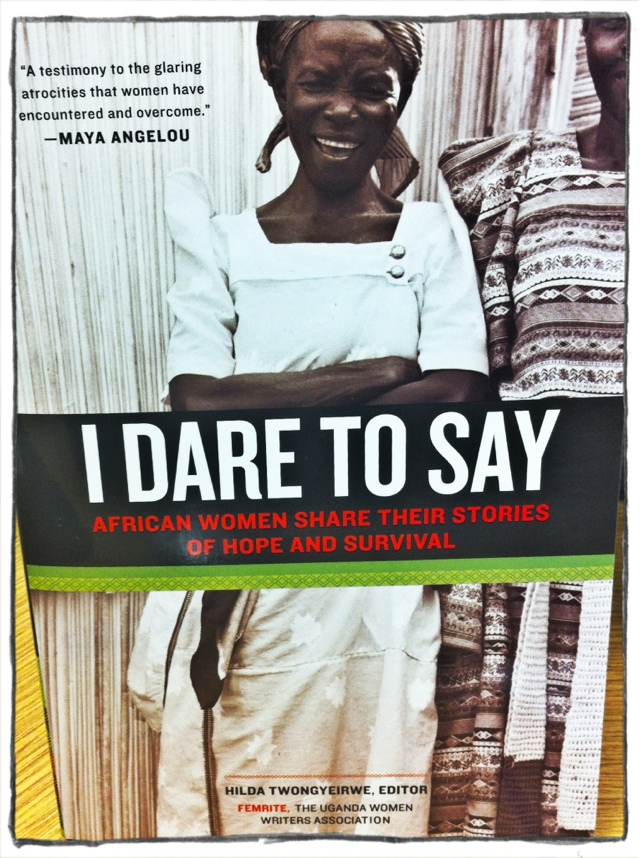

“I Dare to Say” Book Review: A Lesson in Hope and Resilience from African Women

My mother was the kind of woman that would toss harsh truths at you from the other end of the dinner table right before asking you to pass the salt. “I Dare to Say†captures the reality of that kind of resilience – the kind that has learned to live…