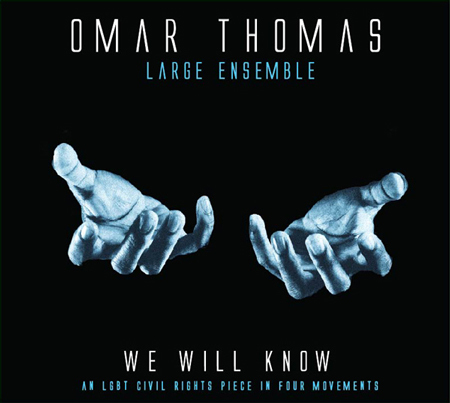

Interview with Omar Thomas, Jazz Composer of Monumental LGBT Civil Rights Hymn, “We Will Know”

I recently got the chance to interview award-winning composer, Omar Thomas, about his new album, ‘We Will Know’, a monumental work of art that breathes new life into the word “movement”.

Following the success of his debut release, I Am, Omar secured a grant in 2013 to compose, arrange, and produce an album to reconcile the perceived incongruities between LGBT and Black communities in the United States.

Per the virtual release event, existing at the intersection of black civil rights and LGBT civil rights, “We Will Know” is a historic, first-of-its-kind original work which invokes genres of music unique to the black American experience as a way of underscoring the experiences of LGBT persons in America over the past 90 years.

In Omar’s artist statement, he states: “The beauty and madness of this work is that it is a composition based on juxtaposition, promoting a social movement written in a genre (jazz) pioneered by a group that historically has an aversion to the group for which the piece is created. Though it is written in solidarity with the LGBT movement, it is anchored by styles and songs created by and for the African-American experience.”

Each of the four movements plays a specific role in framing the realities of LGBT persons across the country.

- The first movement, “Hymn,” is a rallying protest song – that glue which holds together all significant social movements – which the LGBT movement has been without for all these years.

- The second movement, “In Memoriam,” is a brief elegy that commemorates the lives of those lost and those facing real danger in the face of ignorance and fear.

- The longest of the movements, “Meditation,” provides the listener a safe place for reflection and catharsis.

- And, the final movement, “May 9th, 2012,” combines the original hymnsong with Charles Albert Tindley’s iconic black civil rights song, “We Shall Overcome,” to celebrate the day an American president (and also our first black president) first publicly supported marriage equality.

LGBT civil rights are at the forefront of contemporary social and political discourse. The power of music to serve, inspire, and archive movements is a necessary part of that conversation, one that Omar Thomas, a hauntingly talented musician and self-described ‘artivist’ is committed to facilitating through his music.

On Music, Movements, and Identity: Interview with Black and Gay Composer, Omar Thomas

SPECTRA: I’m gonna get right into it… “We Will Know: An LGBT Civil Rights Piece in Four Movements.” That’s a bold title! And, if I must say, such a beautiful gift to black LGBT people, or any of us who live our lives at the intersection. What inspired the project?

OMAR: I got the idea to compose an LGBT civil rights piece after numerous failed attempts at sounding intelligible on an “It Gets Better” video.

SPECTRA: No… Haha! Really?

OMAR: True story. I really wanted to contribute to the message and success of the “It Gets Better” campaign, but couldn’t find the words. I’m not a writer. I’m a musician. So it dawned on me in that moment — that music is a language at which I’m adept, my chosen language of love and protest. I mean, clearly I was failing so miserably in English while trying to make that video. So I decided right then and there that I’d made my contribution to groundswell of awareness and support – “the movement’ – using my natural talent: music.

SPECTRA: Mmm, I love that. It’s a really beautiful thing to witness someone stepping so boldly into their purpose. Did you ever imagine you would release an album like this?

OMAR: To be able to communicate so effectively using music is a gift. It only made sense that my contributions to human rights take the form of a musical statement. And honestly, the creation of this piece felt inevitable, really, as if my growth as a composer, educator, and socially-conscious citizen were all leading to the creation of this work.

SPECTRA: This is your second album. Your first won a Boston Music Award in 2013 for Best Jazz Artist. You’ve called ‘We Will Know’ one of your most important pieces of work to date. What hopes do you have for the EP?

OMAR: From the side of the music, I hope the movements in ‘We Will Know’ highlight the gamut of emotions that have underscored the LGBT civil rights struggle – and triumphs – of the past century. I want the experience of listening to the album to feel like catharsis, of the personally political kind.

SPECTRA: The album is definitely a conversation starter.

OMAR: Music is a commonality we all share. It’s just one of many, many commonalities we all share. And its universality makes it the ideal ambassador for the connections we share across experiences. And its convening power bring us all closer to the ideas of oneness, a singular human story that I truly believe is at the nucleus of the human experience.

SPECTRA: Omar, you teach “Harmony” at Berklee College of Music. (smile). Can you explain – to those of us with a limited jazz vocabulary — what that means? Listening to you talk about music, movements, and unity, it seems fitting as the name of a class you would teach!

OMAR:Â *laughs* Harmony at Berklee College of Music is the study of contemporary music theory. The study of melody, harmony, and rhythm in popular song. As music mirrors life and vice versa, I always find creative ways to discuss various aspects of life in my classes.

SPECTRA:Â Speaking of teaching, has your identity as a black gay man influenced or impacted your role as an educator in any way?

OMAR: I’d like to think it has been positive. I have a simple personal mandate: to live authentically and to do the best I can, as an educator, as a musician, and as a citizen, so that those who feel empowered by the labels of “gay,” “black,” and the combination of the two will feel seen, uplifted. I’m not the only gay black musician out there. There are many who came before me, whose shoulders I stand on, and more will come afterwards. I honour them by being visible.

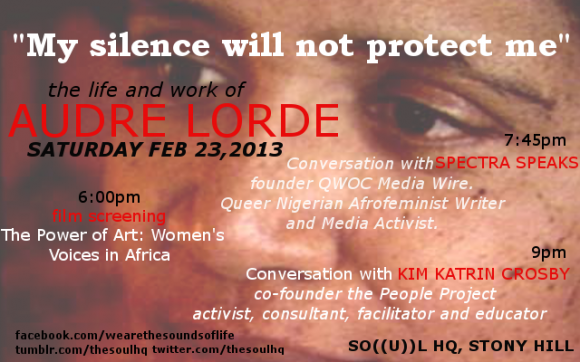

SPECTRA:Â Somewhat related. On visible black and LGBT icons. Each year during black history month, I see the same names of Black and LGBT leaders mentioned e.g. James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Bayard Rustin etc. Many writers, political activists etc. As a young, gay, black, and aspiring musician, who did you look up to?

OMAR:Â Billy Strayhorn. Hands down. The right hand man to the great Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington. So great was his talent, his poise, and his presence that literally no one cared about his orientation. Okay, maybe they did but they got over it. Who knows. I’m sure he had his own share of struggle. But he never minced words about his sexuality, nor did her ever hide. In the early half of the 20th century. In America. As a black man. As a gay, black man. What courage! His story has always resonated with me.

SPECTRA:Â I have to ask… especially given that you’re a black and gay musician who’s just released an EP calling for equal rights. And Macklemore just won a Grammy for Same Love. Where do you stand on musical accolades being about the music vs. the political messages they convey? Can we, actually, separate them?

OMAR:Â For me, being a musician, or a chef, or a writer, or a painter, or a dancer, is all about authenticity and vulnerability. If one’s art is to ring true, one’s identity must ring true THROUGH one’s art.

Anyone who is using their voice to further ideas of universality and oneness deserves to be commended, but only if they do so with respect to context, meaning where their contribution fits in the narrative of those who’ve come before them in this fight.

That being said, a positive message is a positive message, and good music is good music. These two concepts are mutually exclusive. If a work is to be critiqued based on the strength of its message, then so be it. If it is to be critiqued on its musical strengths and merits, so be it. If both are present and are formidable, all the better.

SPECTRA:Anything else you’d like folks to know?

OMAR:Â I’m encouraging everyone to start using the hashtag #iamtheintersection to continue the dialog about multiple identities, shared history, and oneness. You can follow me at @omarthomasmusic on Twitter and Facebook/omarthomasmusic to join the conversation.

Do yourself a favour and listen to the first movement, “Hymn” below. (I’m in tears every single time!)

‘We Will Know: An LGBT Civil Rights Piece in Four Movements’ is now available for purchase on iTunes. A limited number of commemorative physical copies, which include comprehensive 4-page timeline of milestones of the LGBT movement over the past century, are also available for order on the official Omar Thomas website, www.omarthomasmusic.com.

Love birds Tshepo Modisane and Thoba Sithole, both proudly Zulu and Tswana, have made their union a part of South Africa’s history by deciding to go public with their gay African traditional wedding ceremony, with a few twists:

Love birds Tshepo Modisane and Thoba Sithole, both proudly Zulu and Tswana, have made their union a part of South Africa’s history by deciding to go public with their gay African traditional wedding ceremony, with a few twists: Chimamanda Adichie, a celebrated Nigerian writer said in her famous TEDTalk, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes, is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.â€

Chimamanda Adichie, a celebrated Nigerian writer said in her famous TEDTalk, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes, is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.â€

During the event, this disclosure prompted more questions (and conversation) about what it means to build sustainable movements. After all, so many of us have  been spurred to action by painful and, at times, traumatic experiences: how do we continue to drawn from such turbulent beginnings without letting them weigh us down emotionally?

During the event, this disclosure prompted more questions (and conversation) about what it means to build sustainable movements. After all, so many of us have  been spurred to action by painful and, at times, traumatic experiences: how do we continue to drawn from such turbulent beginnings without letting them weigh us down emotionally?