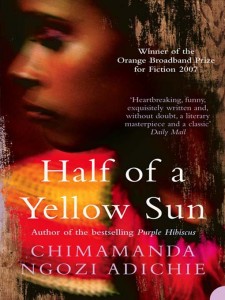

Africa has had much of its history depicted through mainly male characters; the on-going plight of women and children during times of war has often been reduced to b-roll (i.e. supplemental or alternate footage intercut with the main shot) and action scenes portraying sexual violence for shock value. Hence, the…

-

-

Not (Just) Another Queer Movie: My Afrofeminist Review of Pariah

Wait a minute, not all lesbians in movies are white, rich or middle-class with no bills to pay? You mean “life†doesn’t get put on pause so that all gay people can experience the thrill of coming out at summer camp? And, there are other LGBT issues worth talking about…

Online rulet oyunları gerçek zamanlı oynanır ve online slot casino bu deneyimi canlı yayınlarla destekler.

Türkiye’deki bahisçilerin güvenini kazanan bettilt giriş hizmet kalitesiyle fark yaratıyor.

İnternet üzerinden eğlence bahsegel giriş arayanlar için deneyimi vazgeçilmezdir.

Kullanıcıların hesaplarına hızlı ve sorunsuz bettilt ulaşabilmesi için adresi her zaman güncel tutuluyor.