I don't doubt for one second that criticism of Hollywood plays an important role in keeping Hollywood accountable. But black women owe it to each other to more frequently use our voices to highlight our resistance, our power, ways in which artists of color have been resourceful, increasing support and…

-

-

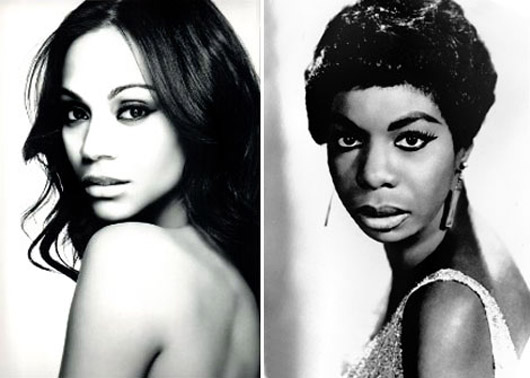

Zoe Saldana to Star in Nina Simone Biopic: How the Dark vs. Light Skin Debate Misses the Point about Black Women and the Media

In case you missed it, Hollywood is gearing up to release a biopic of Nina Simone, an African-American singer, pianist, and civil rights activists whose music was highlight influential in the fight for equal rights for blacks int he US. Zoe Saldana, a light-skinned Dominican actress has been cast to…

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Creative Corner - Gender and LGBT Issues - Movement-Building - Poetry - Race, Culture, Ethnicity - Thought Leadership

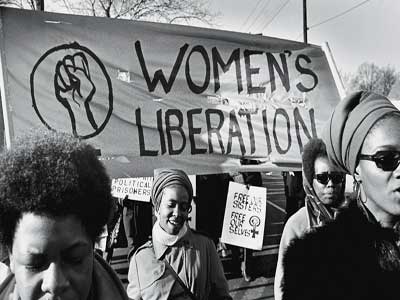

Reflections from a Woman of Color on the War on Women: “My Sisters-in-Arms, We Are Not United”

I'm sharing the remarks I gave at the MA Women United Against the War on Women rally in Boston (in poem-ish form). I found myself thinking about the concept of "unity," and the fact that so many women of color, immigrants, transgender women etc are often left out of mainstream…

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Film - Gender and LGBT Issues - LGBT Africa - Media - Race, Culture, Ethnicity - Social Commentary - Special Series

Racism and LGBT Rights: Where are the African Films in the South African LGBT Film Festival?

South Africa's 19th Out in Africa LGBT Film Festival opens this weekend and there is certainly no shortage of films about women, quite an achievement to note given how often the LGBT community is depicted as male. Yet, within the context of Africa, the LGBT community is also frequently perceived…

-

Not (Just) Another Queer Movie: My Afrofeminist Review of Pariah

Wait a minute, not all lesbians in movies are white, rich or middle-class with no bills to pay? You mean “life†doesn’t get put on pause so that all gay people can experience the thrill of coming out at summer camp? And, there are other LGBT issues worth talking about…

Online rulet oyunları gerçek zamanlı oynanır ve online slot casino bu deneyimi canlı yayınlarla destekler.

Türkiye’deki bahisçilerin güvenini kazanan bettilt giriş hizmet kalitesiyle fark yaratıyor.

İnternet üzerinden eğlence bahsegel giriş arayanlar için deneyimi vazgeçilmezdir.

Kullanıcıların hesaplarına hızlı ve sorunsuz bettilt ulaşabilmesi için adresi her zaman güncel tutuluyor.