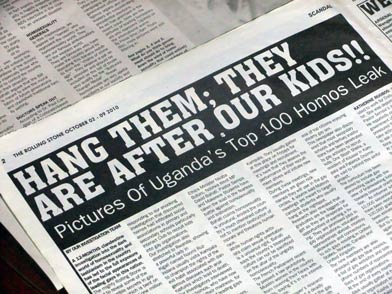

But now, the draconian bill which began the chain reaction that led to David Kato's death is back. A copy of Uganda's Parliament Order Paper, dated February 7, 2012, has been making its way around the internet. The return of the "Kill the Gays" bill is a major concern for…

-

-

Challenging Gender Binaries in the Motherland: Could Transgender and Intersex Activism Unite Africa’s Movements?

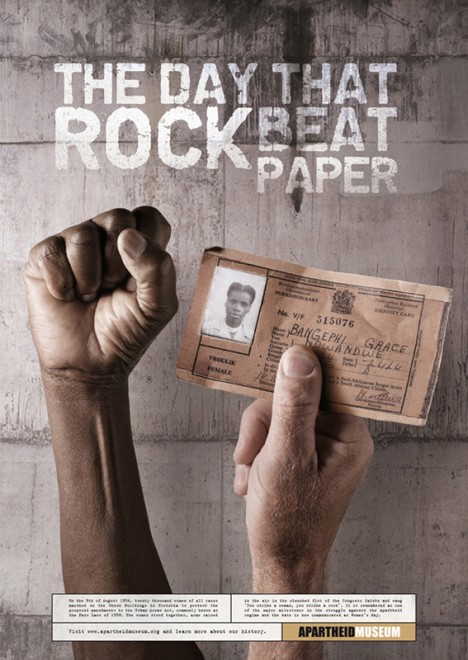

The existence of LGBT Africans ultimately challenges the view that Africans are naturally attracted to people of the opposite sex (i.e. the Homosexuality is UnAfrican mantra). However, this pigeon-holes the entire continent — straight and LGBT Africans alike — into addressing homophobia from just one angle: sexual orientation. The danger…

-

Advocacy - African Feminism - Afrofeminism - Blog - Gender and LGBT Issues - International Development - LGBT Africa - Media - Non-Profits - Philanthropy

Saying No to Media Saviorism, Celebrating Africa’s Resistance

How about we — as global gender justice advocates — subvert the idea that women are perpetual victims by covering our collective resistance? How about we cut back on the sensationalism — the shock tactics and controversy we once deployed to get mainstream media to pay attention to issues important…

-

Not (Just) Another Queer Movie: My Afrofeminist Review of Pariah

Wait a minute, not all lesbians in movies are white, rich or middle-class with no bills to pay? You mean “life†doesn’t get put on pause so that all gay people can experience the thrill of coming out at summer camp? And, there are other LGBT issues worth talking about…

-

Open Letter to LGBT Nigerians and Diaspora: Stand Fast, Change is Coming

They are afraid, of our voices, of our power, of our resiliency. They are afraid of a younger generation of citizens, activists, and diaspora, and our collective belief in a more progressive Nigeria. They are afraid of our growing influence as we gather allies not just from the west, but…

Online rulet oyunları gerçek zamanlı oynanır ve online slot casino bu deneyimi canlı yayınlarla destekler.

İnternet üzerinden eğlence bahsegel giriş arayanlar için deneyimi vazgeçilmezdir.

Kullanıcıların hesaplarına hızlı ve sorunsuz bettilt ulaşabilmesi için adresi her zaman güncel tutuluyor.