I'm sharing the remarks I gave at the MA Women United Against the War on Women rally in Boston (in poem-ish form). I found myself thinking about the concept of "unity," and the fact that so many women of color, immigrants, transgender women etc are often left out of mainstream…

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Creative Corner - Gender and LGBT Issues - Movement-Building - Poetry - Race, Culture, Ethnicity - Thought Leadership

-

African Feminism - Afrofeminism - Blog - Gender and LGBT Issues - International Development - LGBT Africa - Philanthropy - Social Commentary

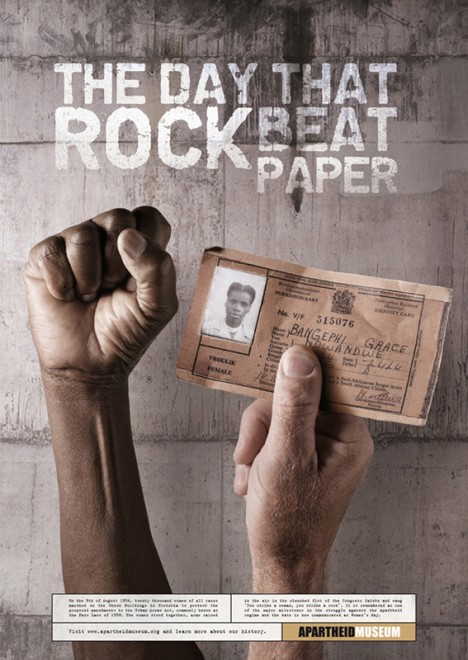

The African Union Protocol on the Rights of Women: Progress and Pitfalls for LGBT Rights

The African Union Protocol on the Rights of Women is the first comprehensive legal framework for women’s rights in Africa that seeks to "improve on the status of African women by bringing about gender equality and eliminating discrimination." Except, it doesn't explicitly name protections for LGBT African women. Moreover, Liberia…

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Film - Gender and LGBT Issues - LGBT Africa - Media - Race, Culture, Ethnicity - Social Commentary - Special Series

Racism and LGBT Rights: Where are the African Films in the South African LGBT Film Festival?

South Africa's 19th Out in Africa LGBT Film Festival opens this weekend and there is certainly no shortage of films about women, quite an achievement to note given how often the LGBT community is depicted as male. Yet, within the context of Africa, the LGBT community is also frequently perceived…

-

Advocacy - African Feminism - Afrofeminism - Blog - Gender and LGBT Issues - International Development - LGBT Africa - Media - Non-Profits - Philanthropy

Saying No to Media Saviorism, Celebrating Africa’s Resistance

How about we — as global gender justice advocates — subvert the idea that women are perpetual victims by covering our collective resistance? How about we cut back on the sensationalism — the shock tactics and controversy we once deployed to get mainstream media to pay attention to issues important…

-

Not (Just) Another Queer Movie: My Afrofeminist Review of Pariah

Wait a minute, not all lesbians in movies are white, rich or middle-class with no bills to pay? You mean “life†doesn’t get put on pause so that all gay people can experience the thrill of coming out at summer camp? And, there are other LGBT issues worth talking about…

Online rulet oyunları gerçek zamanlı oynanır ve online slot casino bu deneyimi canlı yayınlarla destekler.

İnternet üzerinden eğlence bahsegel giriş arayanlar için deneyimi vazgeçilmezdir.

Kullanıcıların hesaplarına hızlı ve sorunsuz bettilt ulaşabilmesi için adresi her zaman güncel tutuluyor.