What Kind of African Doesn’t Speak Any African Languages? Me.

Last year, I attended a conference that brought together African thought leaders. In a session about African identity, we explored the question of whether one could claim to be African without being fluent in any African languages. A passionate, and near disruptive debate ensued almost instantly.

Last year, I attended a conference that brought together African thought leaders. In a session about African identity, we explored the question of whether one could claim to be African without being fluent in any African languages. A passionate, and near disruptive debate ensued almost instantly.

What Language Do You Speak? (aka Do You Speak “Us�)

I’ve had this conversation about language and identity time and again with Africans I meet on my travels. My afropolitan (i.e. world citizen) accent throws them off – a mix of American, Nigerian, and what’s often mistaken for British diction, simply because I enunciate my Ts.  (Perhaps it’s the remnants of attending a British-run primary school; not likely though.). Bread-breaking usually comes to a halt until the matter of my accent (origin) is cleared up. They simply must know which language I speak so that they can place me in one of two boxes: one of us, or one of them.

When I tell the cultural gatekeepers that I’m from Nigeria, and my accent is the result of living in the states for the past 12 years, they’re still not satisfied. “Are you sure you weren’t just born there?” they ask, “You don’t sound like you grew up in Nigeria.” I usually respond by asking them what a Nigerian who grew up in Nigeria sounds like, then hear some variation of “Like the people in Nollywood movies.” And when I tell them, I’m sorry to disappoint, I’m not an actress but an activist, I’m Nigerian through and through–I just went to the states for university, they deliver the kicker, “Well, prove it. What language do you speak?” The minute I respond with English (“Oh…”), it’s all downhill from there.

To Speak or Not to Speak: Assimilation vs. Accents

From tensions in Spain over mandating Spanish (versus indigenous languages like Catalan) to U.S. debates over bilingual education and attempts to ban speaking Spanish at school, the issue of language is a sore spot for many communities. Such language restrictions are often seen as direct attacks on minority cultures, especially for black immigrants who struggle to affirm their cultural heritage in the absence of their native language. Yet, ironically, immigrant parents in the U.S. are less likely to teach their children their native languages, for the purpose – or rather, the sake – of easing their assimilation into English-speaking culture.

From tensions in Spain over mandating Spanish (versus indigenous languages like Catalan) to U.S. debates over bilingual education and attempts to ban speaking Spanish at school, the issue of language is a sore spot for many communities. Such language restrictions are often seen as direct attacks on minority cultures, especially for black immigrants who struggle to affirm their cultural heritage in the absence of their native language. Yet, ironically, immigrant parents in the U.S. are less likely to teach their children their native languages, for the purpose – or rather, the sake – of easing their assimilation into English-speaking culture.

The latter scenario resonates deeply with me. I grew up with a father who wasn’t fluent in his mother tongue, Agbor (a region-specific dialect of Ika), because his father had outlawed the language being spoken in the house. My grandfather–who worked as a civil servant during Nigeria’s colonial era–had valid reasons for doing so. In those days, speaking “proper” English meant you got the “good jobs,†which meant increased access to resources, and an improved livelihood for one’s family. Sadly, even though my father openly resents never having learned his family’s language, his wife–my mother–refused to teach me her native tongue, Igbo, for a similar reason.

Colonialism did a number on Nigeria’s education system; as I was growing up, public schools were plagued with lack of resources, frequent strikes, cult violence, sexual harassment, and prostitution. Hence, my mother’s desire to see me succeed meant equipping me with tools to ensure I could thrive outside of the country I called my home. For instance, I would attend an international British-run private school, where white teachers would single out the only other black kid in the class for not pronouncing “stomach†correctly ( “stuh-muckâ€, not “stoh-mack†apparently); only an American or British university would do; I would not learn my native tongue until I spoke English “perfectly†and no longer risked picking up a “bad, Nigerian accent†that would make it harder for me “over there.â€

Colonialism did a number on Nigeria’s education system; as I was growing up, public schools were plagued with lack of resources, frequent strikes, cult violence, sexual harassment, and prostitution. Hence, my mother’s desire to see me succeed meant equipping me with tools to ensure I could thrive outside of the country I called my home. For instance, I would attend an international British-run private school, where white teachers would single out the only other black kid in the class for not pronouncing “stomach†correctly ( “stuh-muckâ€, not “stoh-mack†apparently); only an American or British university would do; I would not learn my native tongue until I spoke English “perfectly†and no longer risked picking up a “bad, Nigerian accent†that would make it harder for me “over there.â€

You see, both my parents studied in Los Angeles in the 70s; on top of the (incomprehensible to me) racism of the time, they also faced American imperialist views and discrimination against “foreigners.†My mother was repeatedly rejected by employers for speaking too “harshlyâ€, eventually forcing her to give up pursuing her dream career in television. It’s no wonder that every morning in my early childhood, my parents would wake up at 5 am to tape Satellite episodes of Sesame Street…They believed (or hoped) that watching British and American English programming would teach their children to speak “properly,†so they wouldn’t have to give up on their dreams.

The Blame Game: Colonialism, Forced Migration, and “Bad African Parentsâ€

For a long time, I resented my parents for robbing me of learning both my native languages. Later, I resented Nigeria for being so poorly-run that my parents couldn’t see me thriving anywhere but outside of it. Now, as I think about the players who created the environment I was raised to escape–who concocted a system so cruel it culturally orphans children for its own purposes, it’s become much harder to keep directing anger at my own family, and my own people.

For a long time, I resented my parents for robbing me of learning both my native languages. Later, I resented Nigeria for being so poorly-run that my parents couldn’t see me thriving anywhere but outside of it. Now, as I think about the players who created the environment I was raised to escape–who concocted a system so cruel it culturally orphans children for its own purposes, it’s become much harder to keep directing anger at my own family, and my own people.

My parents shouldn’t be crucified for acting in full awareness of the unjust systems that police indigenous cultures: the colonialist rubble left behind in Nigeria by the British Empire, and the resentment of Britain’s imperialist younger brother, the US of A, towards foreigners. Their fears were rational. Even today, my Puerto Rican partner, who manages a Spanish-speaking client support team at work, comes home at least once a week to vent about some caller’s rude reaction to a supervisee’s accent, dismissing them as un-educated, or ill-equipped to perform their jobs because they perceivably don’t speak “proper English.â€

Still, while many immigrants are forced to sacrifice native language fluency, it’s important to note that similar negotiations around language, identity, and yes, accents, don’t just play out within the context of the migrant Diaspora. Many Africans living on the continent don’t speak their native languages, either. And, their reasons aren’t so different from their estranged brethren.

In Nigeria, for instance, as a Delta-Igbo person living in a state dominated by Yorubas, I experienced much discrimination at school: regular tribalist diatribes from Social Studies teachers, punctuated by stereotypical Igbo impersonations from classmates.

The ethnic tensions that permeated my school dated back to when Igbo people had attempted to gain independence from the political mess the British left in Nigeria post-independence. These attempts, the result of colonial powers leaving certain ethnic groups in power over others, led to the Biafran war and genocide. The war had a lasting legacy: many Igbo students at my school didn’t speak their language (openly) for fear of being socially ostracized. Speaking, or at least understanding even broken Yoruba was a way of appearing more socially acceptable, to assimilate and survive.

Policing Africanness: Language, Globalization, and Cultural Access

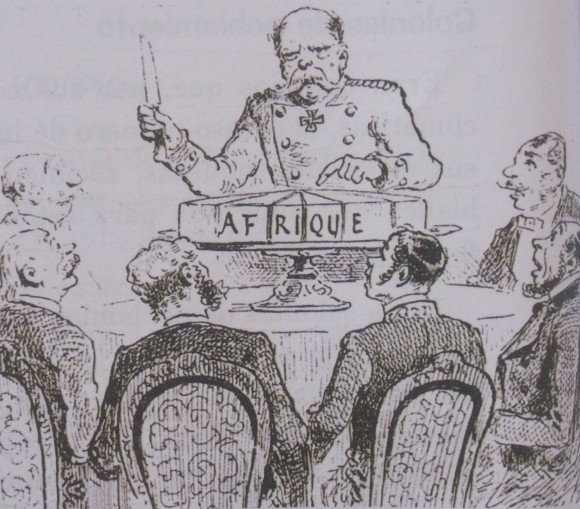

As is the case with many other colonized African countries, in South Africa, for example, the 12 official languages are the result of white men sitting down at a table, drawing squiggly lines around the region they wished to claim. They didn’t care about the diversity of peoples living there: not when they declared Afrikaans the official language of schools during apartheid, and not now when discussing the “under-achievement” of black youth while ignoring the impact apartheid’s indifference to Africa’s diverse cultures and languages has had on the struggle to reform education.

By the way: Afrikaans is not an indigenous African language, its origins date back to Europe settlers who spoke Dutch. Yet, there are South Africans (coloreds and blacks) who only speak Afrikaans or English due to similar circumstance e.g. migration, globalization, interracial adoption, etc.  Are they “less African” than the Black South Africans who speak indigenous languages such as Xhosa? Or Zulu? What about white people who migrate to Africa and learn to speak local languages? Are they now “more African” than Africans who do not, yet have been living in Africa  since birth?

Chill Out: Language is Just One Aspect of Culture

My purpose isn’t to debate who is more African than whom based on language fluency (or even geopolitical circumstance). On the contrary: I don’t understand how anyone can cherry pick a single aspect of our culture as the arbiter of “authentic” African identity: Language. For sure, it’s important. But so is indigenous spirituality, traditional garb, family values, the arts. Culture comprises many elements, thus it makes no sense to police cultural belonging– cling to such a divisive hierarchy, based on the single factor of language, especially considering the lasting effects of our colonial history, and the impact of globalization on contemporary African culture.

I am also not using colonialism as an excuse to lessen the importance of learning our native tongues; language offers us a very obvious, easily detectable signal that someone is either part of our community, or not. You know this if you’ve ever walked into a Dominican bodega and had to ask for something in English, then watched as the eyes computed, instantly: “not one of us.” Furthermore, in many African cultures, the parts of our history that haven’t yet been erased or revised are passed down to younger generations, orally. In political protest, Fela Kuti, father of “Afrobeat”, and one of Africa’s most celebrated music icons, wrote most of his songs in pidgin in order to connect with the lay man who didn’t speak “proper English.â€Â His son, Femi Kuti, has carried that tradition forward, and with that, Fela Kuti’s legacy. Indigenous languages safeguard our stories in their hidden meanings and subtext, so much so that the mis-translation of a single word can create a completely different interpretation of history as we know it, and we’d literally lose ourselves.

Perhaps that’s why we stubbornly stick to fluency in “our mother tongues” as the yardstick for measuring “Africanness,” “our-ness,” “us-ness.†Perhaps the tune about real Africans being able to speak their mother tongues is only sung in protest against the hegemony of our colonizers’ languages. But is spiting them reason enough to spite each other? By perpetuating the use of a single cultural marker to create an hierarchy of Africanness, aren’t we simply deploying the same tools colonizers used to divide and conquer? Aren’t we essentially continuing the work the British Empire started?

We can do better.

There are a myriad of other identity markers that reveal the extent of both our sameness and uniqueness and make up the diverse African cultures that span the globe. Africa is complex–Africans, even moreso. Let’s not trade in our shared heritage for the exclusivity of an unjust social hierarchy. Let’s not , as our colonizers did, draw borders around poorly constructed monoliths. Our just protest for an Africa with linguistic agency must not turn us into the same masters of imperialist dogma we’re still yet to hold accountable.

——-

Update: Line which initially said there exist South Africans who only speak English or Afrikaans has been updated to contextualize loss of indigenous/mother tongue language fluency happening due to globalization, migration, cross-cultural adoption, and other factors so as not to perpetuate that as the norm. (Thanks MR for helping me clarify!)

During the event, this disclosure prompted more questions (and conversation) about what it means to build sustainable movements. After all, so many of us have  been spurred to action by painful and, at times, traumatic experiences: how do we continue to drawn from such turbulent beginnings without letting them weigh us down emotionally?

During the event, this disclosure prompted more questions (and conversation) about what it means to build sustainable movements. After all, so many of us have  been spurred to action by painful and, at times, traumatic experiences: how do we continue to drawn from such turbulent beginnings without letting them weigh us down emotionally?

Y-Fem’s mission is to nurture the next generation of feminist leadership. Pow! These inspiring young women I was privileged to spend two weeks with in Namibia describe themselves as “an organization that creates space for passionate, stylish, and fashionable young Namibian women and allies.” Ooh la la — sign me up! This is exactly what we need — an organization that isn’t afraid to make feminism cool, fashionable. During my sessions with them, it came up, over and over again, that they were committed to making sure Y-Fem appealed to the ‘every day’ girl, not just women’s and gender studies major. Incidentally, I got to help them prepare for their first major event, which was an informal social gathering intended to create an awareness of feminist and women’s issues through the use of poetry by both established and aspiring poets. They pulled that event off like pros; I arrived mid-way through it to find 40+ people gathered around a blazing fire as a woman chanted and sang about her love for African women. Namibia’s women’s movement is in good hands if Y-Fem has anything to say about it.Â

Y-Fem’s mission is to nurture the next generation of feminist leadership. Pow! These inspiring young women I was privileged to spend two weeks with in Namibia describe themselves as “an organization that creates space for passionate, stylish, and fashionable young Namibian women and allies.” Ooh la la — sign me up! This is exactly what we need — an organization that isn’t afraid to make feminism cool, fashionable. During my sessions with them, it came up, over and over again, that they were committed to making sure Y-Fem appealed to the ‘every day’ girl, not just women’s and gender studies major. Incidentally, I got to help them prepare for their first major event, which was an informal social gathering intended to create an awareness of feminist and women’s issues through the use of poetry by both established and aspiring poets. They pulled that event off like pros; I arrived mid-way through it to find 40+ people gathered around a blazing fire as a woman chanted and sang about her love for African women. Namibia’s women’s movement is in good hands if Y-Fem has anything to say about it.