“I Dare to Say” Book Review: A Lesson in Hope and Resilience from African Women

I first learned about “I Dare to Say”, a new anthology of African women sharing their stories of hope and survival, after I’d recently decided that, when it came to writing about Africa, I would only ever highlight stories of struggle alongside resistance.

I first learned about “I Dare to Say”, a new anthology of African women sharing their stories of hope and survival, after I’d recently decided that, when it came to writing about Africa, I would only ever highlight stories of struggle alongside resistance.

Incidentally, I’d also just published a response to the Kony 2012 campaign about the need for more African women’s voices in the media. Needless to say, the publication of this anthology by FEMRITE, the Ugandan Women’s Writers Association, was timely.

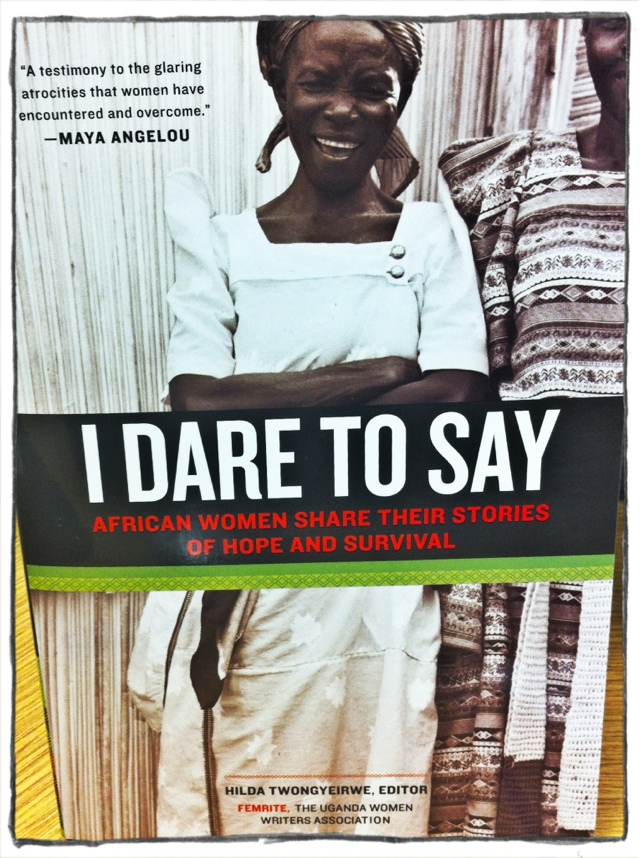

When my copy arrived in the mail, I felt a sense of pride staring at the glossy cover, a sepia photo of two older African women dressed modestly in old garments. Something about the woman in the foreground felt familiar, wrinkles on her bare forearms, wearing the kind of smile that only follows after a really good laugh.

A month later, I realized it had been the memory of both my grandmothers that the image had invoked; they too masked a lifetime of pain and perseverance behind bright white smiles in the sepia photos of my family’s history, their stories held captive within fading images of moments when they temporarily forgot their burdens.

I had once felt I could never know what my grandmothers (and even my own mother) suffered at the hands of poverty, the unforgiving hand of patriarchal traditions, and Nigeria’s bloody civil war. I’d for a very long time resented my mother for her matter-of-fact way of moving through life, never stopping long enough to share the details with an eager first daughter who yearned for a deeper connection with the women in her family; I spent my childhood yearning for stories that lived beyond the slew of parental commands that came infused with generations of gendered duty.

My mother was the kind of woman that would casually toss harsh truths at you from the other end of the dinner table, right before asking you to pass the salt. “I Dare to Say†captures the reality of that kind of resilience – the kind that has learned to live in the next second, the next minute, the next day, never having had the luxury of sitting on a rock for timed introspection; the kind that’s learned to convert detachment into the instinct to keep breathing despite the suffocating feeling of hopelessness.

Reading the book itself was a lesson in perseverance; the longer I paused between stories, the harder it was to bring myself to brave the next one. So, onward I would press on, carrying all the pain, anger, frustration, and chest-heavy burden from being triggered by these women’s experiences, reliving their trauma with them.

Through tears and turning pages, I would question everything I believed: whether I was truly grateful for the life I was currently living or gorging my ego with self-pity, whether or not the work I was currently doing as an activist was meaningful, given how few of these women it touched. I would feel myself shutting down, wanting to close my heart to further pain by closing the book, and in essence, silencing these women’s voices.

But when African women facing overwhelming hardship and circumstances, re-live their trauma to share their journey with us, in order to engage us, educate us, even heal us, we owe them more than a few brief moments of empathy; we owe them our undivided attention, our gratitude, and our commitment to holding on to the voices and their stories as though lives depend on it; because they absolutely do.

“I Dare to Say†not only reveals to the reader, the unrelenting burden of resilience that comes with living in some of the most impoverished areas and under the most debilitating circumstances in Africa, but its first-hand accounts by Ugandan women offer poignant insight into some of the most prominent issues facing women all over the world today.

Here are a few reasons why this groundbreaking collection should be gifted, purchased, and read by every women’s and gender studies department, every single African feminist, every human rights activist, every father, brother, and uncle, everywhere:

1) Concise, Clear Focus on Concrete Set of Issues:Â Rather than attempt to cram the myriad of issues facing African women into a dense and overwhelming product, this anthology focuses on the ones tied to culture and tradition, and thus are often stigmatized, making their exploration more powerful. The editors organized the collection into four distinct sections:

- Tears of Hope: Surviving Domestic Abuse

- Farming Ashes: Tales of Agony and Resilience (Post-Conflict)

- I Dare to Say: Facing HIV/AIDS

- Beyond the Dance: The Torture and Trauma of Female Gential Mutilation.

2) Stories Remain Powerful When Read in Order or At Random: I read the stories in order, from start to finish. I must confess, however, that even though I initially believed the sections would prepare me for what was to come, each story felt like a different emotional expedition, raw and unexpected. So, I’m not sure how different the experience would be for a reader who opted instead to select stories at random. Nonetheless, the modular way in which the narratives were presented, certainly made the context around some of the issues a lot easier to learn and digest.

3) Ethical Curation: This Anthology Honors the Storyteller, Not Just the Story: Each story pays homage to Africa’s long tradition of oral storytelling, by acknowledging the power in both the listener and the person doing the storytelling. In every chapter, the moments leading up to the initial meeting between the writer and the subject are described in first-person and italicized. The interviewer literally holds our hands as they travel on overcrowded buses, walk through villages, and get their subjects to start speaking. When this happens, the narrative voice of the African woman, jolts you into the main story; its rough edges and insights feel raw and uncensored in verbatim, and you can ‘hear’ her, and experience her story as you would if you were right there with her in the room.

Every so often, I meet a book that opens up itself to me in a way that, in turn, encourages me  to be more open with the world about who I am. “I Dare to Say†is one of those books; after reading it, I am forever changed. I feel stronger and prouder than ever to carry the weight of these inspiring women’s stories on my back; their bravery has encouraged me to keep telling my own story, keep fighting for a future in which all our voices are heard, and live from the same place of hope and resilience as the women who have walked this path before me.

Uganda’s first gay pride

Uganda’s first gay pride

I have come to deeply appreciate activists who often have no time to engage in sensationalized international discourse, because they are too busy doing the heavy lifting that comes withÂ

I have come to deeply appreciate activists who often have no time to engage in sensationalized international discourse, because they are too busy doing the heavy lifting that comes with