I don't doubt for one second that criticism of Hollywood plays an important role in keeping Hollywood accountable. But black women owe it to each other to more frequently use our voices to highlight our resistance, our power, ways in which artists of color have been resourceful, increasing support and…

-

-

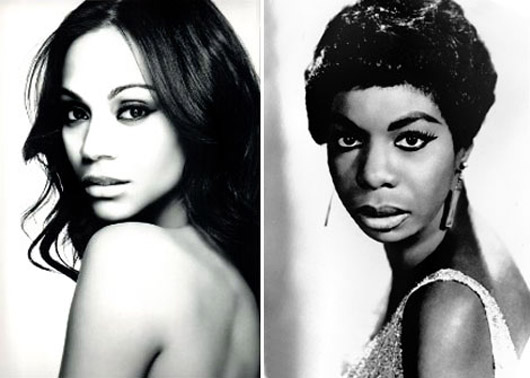

Zoe Saldana to Star in Nina Simone Biopic: How the Dark vs. Light Skin Debate Misses the Point about Black Women and the Media

In case you missed it, Hollywood is gearing up to release a biopic of Nina Simone, an African-American singer, pianist, and civil rights activists whose music was highlight influential in the fight for equal rights for blacks int he US. Zoe Saldana, a light-skinned Dominican actress has been cast to…

-

Our Voices, Our Stories: Training African Women’s & LGBT Organizations to Use Social Media is Critical

Despite the richness, diversity, and complexities that shape the landscape that is my homeland, Africa is often depicted as one big safari (or war zone). Why is that? Because Africa’s stories are rarely told by Africans themselves.

-

Afrofeminism - Blog - Film - Gender and LGBT Issues - LGBT Africa - Media - Race, Culture, Ethnicity - Social Commentary - Special Series

Racism and LGBT Rights: Where are the African Films in the South African LGBT Film Festival?

South Africa's 19th Out in Africa LGBT Film Festival opens this weekend and there is certainly no shortage of films about women, quite an achievement to note given how often the LGBT community is depicted as male. Yet, within the context of Africa, the LGBT community is also frequently perceived…

-

Advocacy - African Feminism - Afrofeminism - Blog - International Development - New Media - Philanthropy - Thought Leadership

We Are Not Invisible: 5 African Women Respond to the Kony 2012 Campaign

I've compiled a list of responses from African women responding to Kony 2012, a controversial campaign launched recently by Invisible Children to raise awareness of child soldiers in Uganda. I'm amplifying their responses because almost overnight, the web became flooded with so much commentary from western media on the erasure…