I decided to tweet about "The Culture of Naming" one evening, and am sharing the archive via this post. My main point was that naming can be as powerful as it can be silencing, and that we should consider the purpose of them before blanket use; for affinity groups, naming…

-

-

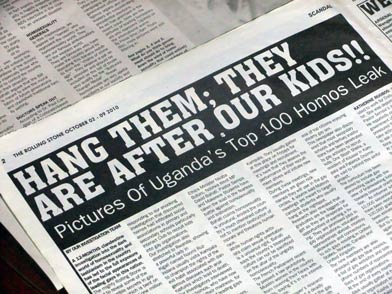

Ugandan LGBT Activists Sue American Evangelist for Inspiring “Kill the Gays” Bill

Scott Lively is one of three American pastors who visited Uganda in 2009 and whom gay activists accuse of helping draft the original version of Uganda’s infamous “Kill The Gays†bill, which called for the death penalty for LGBT people in the country. So now, Sexual Minorities Uganda, a non-profit…

-

3-10 Women Arrested for Being Lesbian in Cameroon: Gender Bias in Anti-Gay Prosecution

Recently, BBC news reported that three women -- allegedly involved in a love triangle -- in Cameroon have been arrested on suspicions of practicing homosexuality. According to the Washington Post, homosexuality is considered criminal in Cameroon and punishable by a jail sentence of six months to five years, plus a…

-

One Year After the Murder of David Kato, Uganda’s Parliament Resurrects “Kill the Gays” Bill

But now, the draconian bill which began the chain reaction that led to David Kato's death is back. A copy of Uganda's Parliament Order Paper, dated February 7, 2012, has been making its way around the internet. The return of the "Kill the Gays" bill is a major concern for…

-

Inspired by Pariah: My Personal Story about Coming Out as a Nigerian “Boi”

As the strapless lilac dress found its awkward place on my body, the delicate layer of my personal confidence dropped mercilessly to the floor.. When my father said I looked "pretty," I immediately went on a dramatic tirade (more dramatic than usual) to assert that this wasn't who I was.…