Growing up in Nigeria, the idea that improving the lives of women was a cause worth fighting for didn't just come from organizations, or brochures, or formal programming; I had strong women around me who constantly put this into practice in the every day, including my own mother.

-

-

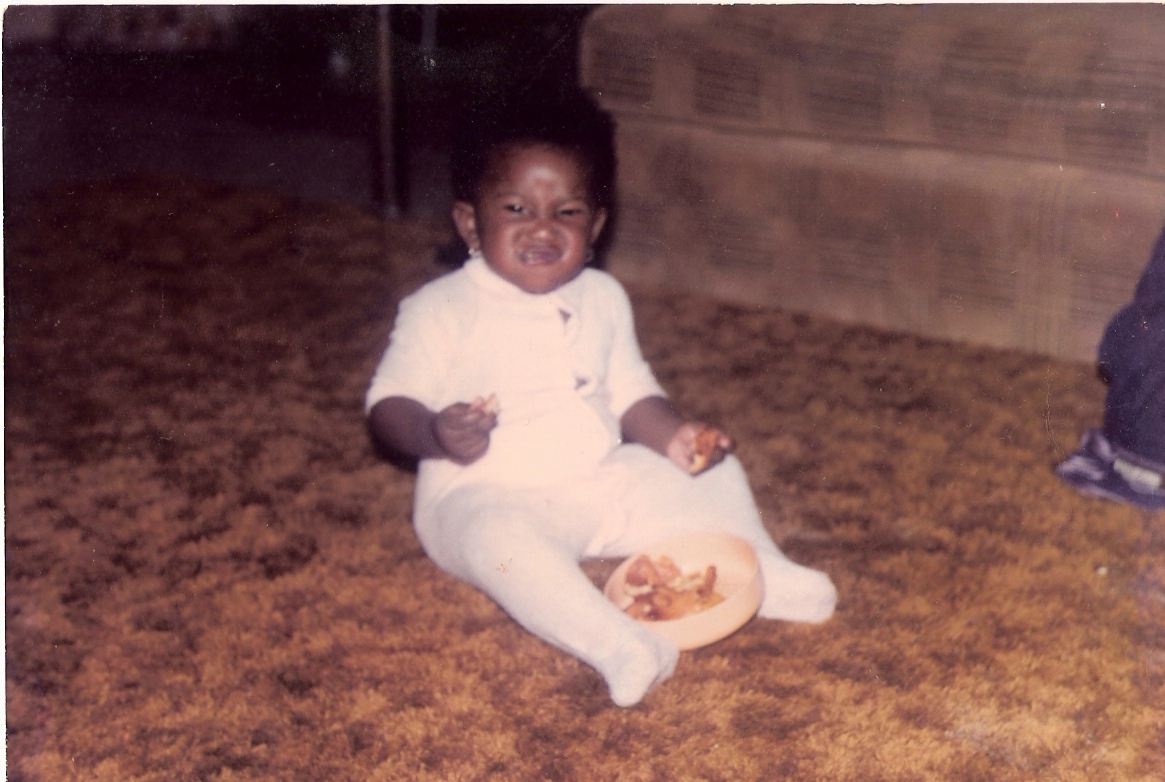

A Brief Herstory: Food Justice and Rebel Toddlers

My mother calls me an exhibitionist, but it's for this reason that I publish so much on the web -- when I'm long gone, I won't have anyone speaking for me, including suggesting that I wasn't always a protesting food justice advocate.

-

Inspired by Pariah: My Personal Story about Coming Out as a Nigerian “Boi”

As the strapless lilac dress found its awkward place on my body, the delicate layer of my personal confidence dropped mercilessly to the floor.. When my father said I looked "pretty," I immediately went on a dramatic tirade (more dramatic than usual) to assert that this wasn't who I was.…

-

My Straight African Brother’s Reflections on a Very Queer Christmas: “Two Couples and a Sibling”

My brother wrote this guest post for me for Christmas and I couldn't be any more moved. For any of you feeling hopeless about your families coming around, I want you to read this and see this as your future, see this as where your own family members could go.…

-

An Immigrant’s Halloween: Blackface, Ghetto Parties, and Disney Princesses

I actually want to have fun during Halloween this year. I don't want to feel constantly triggered by offensive costumes. I actually want to smile at kids when they come trick or treating. I want to carve my first pumpkin without being cheered on by coworkers in blackfaced Bob Marley…

Online rulet oyunları gerçek zamanlı oynanır ve online slot casino bu deneyimi canlı yayınlarla destekler.

Bahis sektöründe adından sıkça söz ettiren Bettilt kaliteyi ön planda tutuyor.

Adres engellerini aşmak isteyenler için pinco casino bağlantısı çözüm oluyor.