African Women in Film: New Screen Adaptation of Chimamanda Adichie’s Novel, Half of a Yellow Sun

There are plans underway for a major screen adaptation project based on one of Nigeria’s most treasured novels, Half of a Yellow Sun.

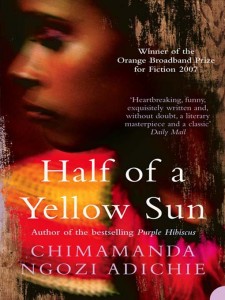

Half of a Yellow Sun, published in 2006, is an award-winning novel by a Nigerian woman author, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It tells the story of two sisters, Olanna and Kainene, during the Biafran War, which began when the Igbos tried to secede as the Republic of Biafra due to political and ethnic struggles among the major ethnic groups — the Igbo, Yoruba, Hausa, and Fulani.

The war lasted for about three years, during which Nigeria cut off all humanitarian aid to Biafra, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Igbo people due to starvation and disease. The effect of the war is shown through the dynamic relationships of four people’s lives ranging from high ranking political figures, a professor, a British citizen, and a houseboy. After the British left Nigeria, the lives of the main characters drastically changed and were torn apart by the ensuing civil war and decisions in their personal life.

Half of a Yellow Sun is undoubtedly one of Africa’s literary gems as it — for once — tells the history of the Nigerian people from the perspective of its inhabitants, and in particular, women and gender during political unrest and times of war. From the novel’s New York Times review:

Like Nadine Gordimer, she likes to position her characters at crossroads where public and private allegiances threaten to collide. Both “Half of a Yellow Sun†and Adichie’s first novel, “Purple Hibiscus†explore the gap between the public performances of male heroes and their private irresponsibilities. And both novels shrewdly observe the women — the wives, the daughters — left dangling over that chasm.

“Half of a Yellow Sun†speaks through history to our war-racked age not through abstract analogy but through the energy of vibrant, sometimes horrifying detail. A refugee flees the north by train, carrying in a bowl her daughter’s head, still bearing its delicate braids. Famished children in refugee camps find themselves unable to outpace and catch lizards. A child soldier, nicknamed Target Destroyer, uses “words like enemy fire and Attack HQ with a casual coldness, as if to make up for his crying.†A girl’s belly starts to swell, and her mother wonders: is she pregnant or suffering from malnutrition?

Africa has had much of its history depicted through mainly male characters; the on-going plight of women and children during times of war has often been reduced to b-roll (i.e. supplemental or alternate footage intercut with the main shot) and fast-cut action scenes portraying sexual violence, it seems, mainly for shock value — as in rape scenes in films like Tears of the Sun and Hotel Rwanda. There are also rarely prominent African women characters who exist beyond their relationship to men. It isn’t often that movie-goers get to experience African women on screen as full, complex characters in the context of their every day lives. Hence, Half of a Yellow Sun, an intricate and emotionally honest story told through the lives of two very different Nigerian sisters, being adapted for film could mean a huge leap for the preservation of Nigerian women’s history, as well as the portrayal of African women in film.

The movie is currently slated to be shot in Nigeria and will be backed by UK producers Andrea Calderwood (The Last King of Scotland) and Gail Egan (The Constant Gardener). Nigerian writer-director, Biye Bandele, has had a hand in the development of the script, and actors Thandie Newton (who is of Zambian heritage) and Chiwetel Ejiofor (Nigerian) are part of a UK cast. So, it seems the film version of Half of a Yellow Sun will take a cue from another recently released black war epic and feature a prominently African cast, which will steer the production crew clear of re-centering the book’s naturally authentic narrative in order to cater to a white and/or western audience (a tactic too frequently deployed in Hollywood films about the diaspora).

The movie is currently slated to be shot in Nigeria and will be backed by UK producers Andrea Calderwood (The Last King of Scotland) and Gail Egan (The Constant Gardener). Nigerian writer-director, Biye Bandele, has had a hand in the development of the script, and actors Thandie Newton (who is of Zambian heritage) and Chiwetel Ejiofor (Nigerian) are part of a UK cast. So, it seems the film version of Half of a Yellow Sun will take a cue from another recently released black war epic and feature a prominently African cast, which will steer the production crew clear of re-centering the book’s naturally authentic narrative in order to cater to a white and/or western audience (a tactic too frequently deployed in Hollywood films about the diaspora).

There have been complaints about prominent actors from Nollywood (Nigeria’s booming film industry) being missing from the cast, as many Nigerians share the sentiment the potential international reach of the film should be used to promote talent from within the country. There’s even a petition to replace Thandie Newton with a Nigerian actress, who may be better equipped to handle all the Igbo that is spoken in the book. Nigerians may not be as pleased with not having Nigerian actors center-staged, but many agree that the story of Biafra — a story that Igbos have fought to protect from erasure by the Nigerian government, and is in further jeopardy of being forgotten entirely due to the passing of one its great political leaders — is a story worthy of a pan-African effort; it simply needs to be told.